피터브뤼겔 BRUEGEL, Pieter the Elder

(b. ca. 1525, Breughel, d. 1569, Bruxelles)

브뤼겔이 살았던 16세기는 르네상스 황금기로,

Pieter Bruegel (about 1525-69), usually known as Pieter Bruegel the Elder to distinguish him from his elder son, was the first in a family of Flemish painters. He spelled his name Brueghel until 1559, and his sons retained the "h" in the spelling of their names.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, generally considered the greatest Flemish painter of the 16th century, is by far the most important member of the family. He was probably born in Breda in the Duchy of Brabant, now in The Netherlands. Accepted as a master in the Antwerp painters' guild in 1551, he was apprenticed to Coecke van Aelst, a leading Antwerp artist, sculptor, architect, and designer of tapestry and stained glass. Bruegel traveled to Italy in 1551 or 1552, completing a number of paintings, mostly landscapes, there. Returning home in 1553, he settled in Antwerp but ten years later moved permanently to Brussels. He married van Aelst's daughter, Mayken, in 1563. His association with the van Aelst family drew Bruegel to the artistic traditions of the Mechelen (now Malines) region in which allegorical and peasant themes run strongly. His paintings, including his landscapes and scenes of peasant life, stress the absurd and vulgar, yet are full of zest and fine detail. They also expose human weaknesses and follies. He was sometimes called the "peasant Bruegel" from such works as Peasant Wedding Feast (1567).

He developed an original style that uniformly holds narrative, or story-telling, meaning. In subject matter he ranged widely, from conventional Biblical scenes and parables of Christ to such mythological portrayals as Landscape with the Fall of Icarus; religious allegories in the style of Hieronymus Bosch; and social satires. But it was in nature that he found his greatest inspiration. His mountain landscapes have few parallels in European art. Popular in his own day, his works have remained consistently popular. Bruegel died in Brussels between Sept. 5 and 9, 1569.

1559 (220 Kb); Oil on oak panel, 117 x 163 cm; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Gemaldegalerie, Berlin

c. 1568 (150 Kb); Oil on wood, 114 x 164 cm (45 x 64 1/2 in); Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

1563 (200 Kb); Oil on oak panel, 114 x 155 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna

c. 1563 (180 Kb); Oil on panel, 60 x 74.5 cm; Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam

1568 (90 Kb); Wood; Louvre

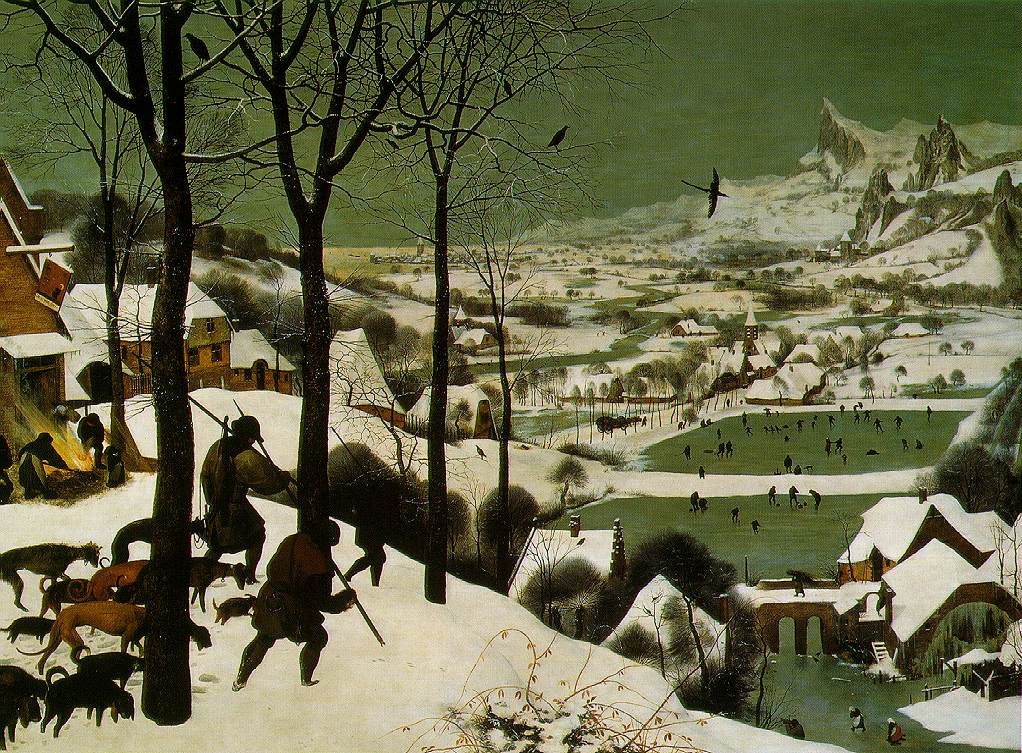

1565 (180 Kb); Oil on wood, 118.1 x 160.7 cm (46 1/2 x 63 1/4 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

1565 (220 Kb); Oil on panel, 117 x 162 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna

c. 1558 (180 Kb); Oil on canvas, mounted on wood, 73.5 x 112 cm; Musees royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels

"이카로스의 추락" 농부는 밭을 갈고, 양치기 소년은 하늘을 보고, 낚시꾼은 났시대를 던지고 있다. 풍경화인듯한데, 오른쪽 하단에 허우적거리는 사람이 이카로스. 제목과 달리 이카로스가 하늘에서 떨러져 추락했는데 소리도 들리지 않고 빠져있는 사람도 본 체 만 체, 사람들의 관심 밖,

'사람이 죽어도 쟁기질은 쉴 수 없다'는 네덜란드의 속담이 들어있는 우의화.

하늘을 날고 싶어하는 인간의 욕망과 미지의 세계에 대한 동경의 대상인

'이카로스의 날개' 이카로스는 고대신화에 등장하는 인물.

이카로스의 아버지 다이달로스는 아테네의 유명한 장인. 다이달로스는 그의 아들에게 날개를 고안해서 탈출계획을 세운다. '너무 높이 날면 밀랍이 녹고 낮게 날면 바다의 물기로 날개가 무거워 지니 하늘과 바다의 중간으로만 날아라' 주의를 주나, 아차 하는 순간 너무 높게 날아 밀랍이 녹아 바다에 추락한다는 이야기. '이카로스의 추락'은 과욕과 오만이 부른 추락.

이카로스의 까만 몸뚱이 속에 붉은 색의 심장이 조그맣게 보입니다. 노란 별빛이 이카로스의

최후를 바라본다.

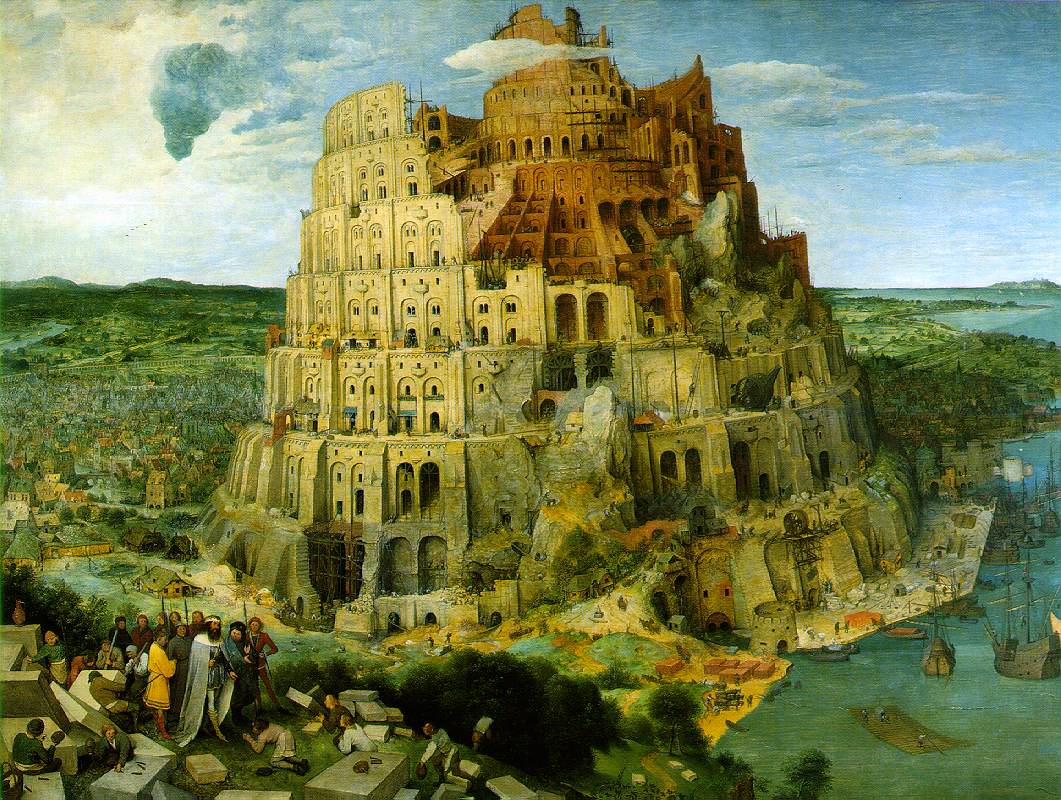

1559-60

Oil on wood, 118 x 161 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

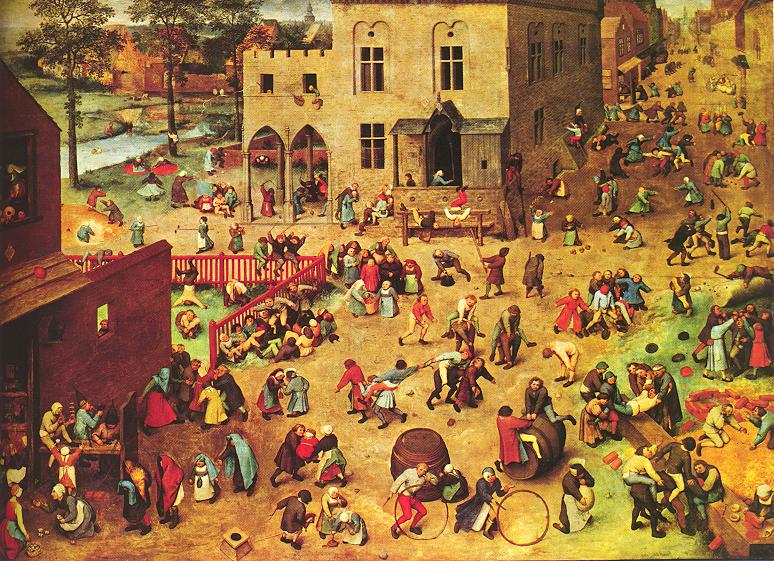

the painting is referred to as the "encyclopaedia of Flemish children's games". It represents about 84 games some of them are practiced until present days. There is also an assumption that the painting is part of a four-piece cycle representing the four seasons.

In addition to the games in the left part of the background a typical Flemish landscape, while on the right a street with excellent perspective can be seen.

Oil on wood, 117,4 x 162 cm

Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp

This painting was mentioned by Carel van Mander in 1604 in his 'Schilderboeck'. He described the principal character of the painting as 'a Mad Meg pillaging at the mouth of Hell / seemingly perplexed / and cruelly and strangely attired', an evil and fearsome woman or witch. Van Mander remained vague about the actual significance of the painting. Perhaps it had already been forgotten by his time. We can be certain, however, that Bruegel gave the work a hidden allegorical or religious meaning, albeit one that remains a mystery. A great many experts have devoted their energies to solving the problem, but none has ever succeeded entirely in explaining the painting. Most of them focus on the possible symbolism of the large woman in the foreground, with her suit of armor, sword, cutlery and money-box. She has been variously interpreted as a symbol of heresy or violence, the personification of hum,an evil and an allegory of instability.

Recently it was proposed that Meg symbolizes Madness, a vice taken in the 16th century to include insanity, rage, gluttony, lust, avarice and ambition, and that the giant figure in the centre of the painting is an allegory of Folly. The additional scenes surrounding the two figures illustrate the causes and repercussions of these two human failings. It was concluded that Bruegel's allegory was intended as an attack on both human nature and the political and religious situation in 16th-century Antwerp.

We could fill a book with suggested interpretations of Mad Meg and it is highly doubtful whether it would bring the viewer any closer to the true meaning of the painting. Nevertheless, the work never fails to fascinate, even without specialist knowledge. No one can fail to appreciate its apocalyptic vision. For that reason, it has also been plausibly interpreted as the Breaking of the Seventh Seal, as recounted in the Book of Revelations. Mad Meg is, indeed, reminiscent of the book of the Apocalypse.

(b. ca. 1525, Breughel, d. 1569, Bruxelles)

브뤼겔이 살았던 16세기는 르네상스 황금기로,

Pieter Bruegel (about 1525-69), usually known as Pieter Bruegel the Elder to distinguish him from his elder son, was the first in a family of Flemish painters. He spelled his name Brueghel until 1559, and his sons retained the "h" in the spelling of their names.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, generally considered the greatest Flemish painter of the 16th century, is by far the most important member of the family. He was probably born in Breda in the Duchy of Brabant, now in The Netherlands. Accepted as a master in the Antwerp painters' guild in 1551, he was apprenticed to Coecke van Aelst, a leading Antwerp artist, sculptor, architect, and designer of tapestry and stained glass. Bruegel traveled to Italy in 1551 or 1552, completing a number of paintings, mostly landscapes, there. Returning home in 1553, he settled in Antwerp but ten years later moved permanently to Brussels. He married van Aelst's daughter, Mayken, in 1563. His association with the van Aelst family drew Bruegel to the artistic traditions of the Mechelen (now Malines) region in which allegorical and peasant themes run strongly. His paintings, including his landscapes and scenes of peasant life, stress the absurd and vulgar, yet are full of zest and fine detail. They also expose human weaknesses and follies. He was sometimes called the "peasant Bruegel" from such works as Peasant Wedding Feast (1567).

He developed an original style that uniformly holds narrative, or story-telling, meaning. In subject matter he ranged widely, from conventional Biblical scenes and parables of Christ to such mythological portrayals as Landscape with the Fall of Icarus; religious allegories in the style of Hieronymus Bosch; and social satires. But it was in nature that he found his greatest inspiration. His mountain landscapes have few parallels in European art. Popular in his own day, his works have remained consistently popular. Bruegel died in Brussels between Sept. 5 and 9, 1569.

1559 (220 Kb); Oil on oak panel, 117 x 163 cm; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Gemaldegalerie, Berlin

c. 1568 (150 Kb); Oil on wood, 114 x 164 cm (45 x 64 1/2 in); Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

He developed an original style that uniformly holds narrative, or story-telling, meaning. In subject matter he ranged widely, from conventional Biblical scenes and parables of Christ to such mythological portrayals as Landscape with the Fall of Icarus; religious allegories in the style of Hieronymus Bosch; and social satires. But it was in nature that he found his greatest inspiration. His mountain landscapes have few parallels in European art. Popular in his own day, his works have remained consistently popular. Bruegel died in Brussels between Sept. 5 and 9, 1569.

1563 (200 Kb); Oil on oak panel, 114 x 155 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna

c. 1563 (180 Kb); Oil on panel, 60 x 74.5 cm; Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam

1568 (90 Kb); Wood; Louvre

1565 (180 Kb); Oil on wood, 118.1 x 160.7 cm (46 1/2 x 63 1/4 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

1565 (220 Kb); Oil on panel, 117 x 162 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna

c. 1558 (180 Kb); Oil on canvas, mounted on wood, 73.5 x 112 cm; Musees royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels

"이카로스의 추락" 농부는 밭을 갈고, 양치기 소년은 하늘을 보고, 낚시꾼은 났시대를 던지고 있다. 풍경화인듯한데, 오른쪽 하단에 허우적거리는 사람이 이카로스. 제목과 달리 이카로스가 하늘에서 떨러져 추락했는데 소리도 들리지 않고 빠져있는 사람도 본 체 만 체, 사람들의 관심 밖,

'사람이 죽어도 쟁기질은 쉴 수 없다'는 네덜란드의 속담이 들어있는 우의화.

하늘을 날고 싶어하는 인간의 욕망과 미지의 세계에 대한 동경의 대상인

'이카로스의 날개' 이카로스는 고대신화에 등장하는 인물.

이카로스의 아버지 다이달로스는 아테네의 유명한 장인. 다이달로스는 그의 아들에게 날개를 고안해서 탈출계획을 세운다. '너무 높이 날면 밀랍이 녹고 낮게 날면 바다의 물기로 날개가 무거워 지니 하늘과 바다의 중간으로만 날아라' 주의를 주나, 아차 하는 순간 너무 높게 날아 밀랍이 녹아 바다에 추락한다는 이야기. '이카로스의 추락'은 과욕과 오만이 부른 추락.

이카로스의 까만 몸뚱이 속에 붉은 색의 심장이 조그맣게 보입니다. 노란 별빛이 이카로스의

최후를 바라본다.

1559-60

Oil on wood, 118 x 161 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

the painting is referred to as the "encyclopaedia of Flemish children's games". It represents about 84 games some of them are practiced until present days. There is also an assumption that the painting is part of a four-piece cycle representing the four seasons.

In addition to the games in the left part of the background a typical Flemish landscape, while on the right a street with excellent perspective can be seen.

Oil on wood, 117,4 x 162 cm

Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp

This painting was mentioned by Carel van Mander in 1604 in his 'Schilderboeck'. He described the principal character of the painting as 'a Mad Meg pillaging at the mouth of Hell / seemingly perplexed / and cruelly and strangely attired', an evil and fearsome woman or witch. Van Mander remained vague about the actual significance of the painting. Perhaps it had already been forgotten by his time. We can be certain, however, that Bruegel gave the work a hidden allegorical or religious meaning, albeit one that remains a mystery. A great many experts have devoted their energies to solving the problem, but none has ever succeeded entirely in explaining the painting. Most of them focus on the possible symbolism of the large woman in the foreground, with her suit of armor, sword, cutlery and money-box. She has been variously interpreted as a symbol of heresy or violence, the personification of hum,an evil and an allegory of instability.

Recently it was proposed that Meg symbolizes Madness, a vice taken in the 16th century to include insanity, rage, gluttony, lust, avarice and ambition, and that the giant figure in the centre of the painting is an allegory of Folly. The additional scenes surrounding the two figures illustrate the causes and repercussions of these two human failings. It was concluded that Bruegel's allegory was intended as an attack on both human nature and the political and religious situation in 16th-century Antwerp.

We could fill a book with suggested interpretations of Mad Meg and it is highly doubtful whether it would bring the viewer any closer to the true meaning of the painting. Nevertheless, the work never fails to fascinate, even without specialist knowledge. No one can fail to appreciate its apocalyptic vision. For that reason, it has also been plausibly interpreted as the Breaking of the Seventh Seal, as recounted in the Book of Revelations. Mad Meg is, indeed, reminiscent of the book of the Apocalypse.

'History of Arts > Renaissance' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 북유럽 르네상스-Hans Holbein the Younger (1) | 2020.05.26 |

|---|---|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo(1527-1593) 프라하... (1) | 2020.05.26 |

| 르네상스전성기 : Raphael라파엘로 (0) | 2020.05.18 |

| 북유럽 르네상스-Hieronymus Bosch(고딕) (1) | 2020.05.18 |

| Titian (0) | 2020.05.18 |