Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn

37살 아내사망, 51살 파산, 63살 아들 죽음, 64살 사망, 100여점의 자화상.

1629 (30 Kb); Oil on canvas; The Mauritshuis, The Hague

1634 (20 Kb); Oil on canvas; Uffizi, Florence

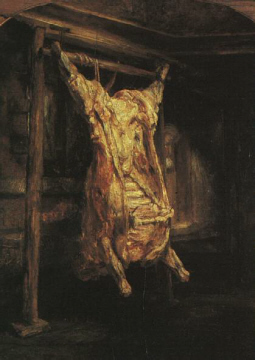

1660 (120 Kb); Oil on canvas, 111 x 90 cm (43 1/2 x 35 1/2"); Musee du Louvre, Paris

1661 (110 Kb); Oil on canvas, 114 x 94 cm; English Heritage, Kenwood House, London

1669 (80 Kb); Oil on canvas, 86 x 70.5 cm; National Gallery, London

<프란스 바닝 코크 대장의 부대>

"Night Watch", 1642; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

<야간 순찰>집단 초상화를 부탁했는데, 그는 마치 무대 위의 주인공과 엑스트라를 그린 것 같은 분위기다. 그러나, 다 같은 돈을 지불했음에도 불구하고, 멀리 얼굴이 분명하지도 않게 혹은 반만 그리거나 뒤돌아있는 사람으로 표현된 사람들은 화가 났다. 그는 더 자연스러운 모습을 연출하기위해 보통의 나열된 집단 초상화에서 벗어나 그의 천재적인 구성으로 오페라의 한 장면을 연출한 것이다.

The Night Watch is misnamed because of a very dark varnish that covered it until the 1940's. It should be titled The Company of Captain Frans Cocq. It is a group portrait of a company of civil guards under the command of Cocq and his lieutenant, Willem van Ruytenburch (in light garb).

This painting was successful. The fact that some members of the company are partially obscured by the action did not cause the work to be condemned, as has been suggested. In this painting Rembrandt solved the problem of the group portrait in such a dynamic way that few after him could ever again sit or stand their subjects in a static line or static grouping. Rembrandt shows Cocq and his men in motion: their lances are askew, their muskets are out of order, and they all project a sense of the vitality of their mission. The canvas is gigantic and was originally even larger. In this group portrait Rembrandt captures the personality of the entire company.

p. 353-354, Humanites: The Evolution of Values by Lee A. Jacobus, (C) 1986 McGraw-Hill.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Rembrandt HARMENSZOON VAN RIJN (b. July 15, 1606, Leiden, Neth.--d. Oct. 4, 1669, Amsterdam), Dutch painter, draftsman, and etcher of the 17th century, a giant in the history of art. His paintings are characterized by luxuriant brushwork, rich colour, and a mastery of chiaroscuro. Numerous portraits and self-portraits exhibit a profound penetration of character. His drawings constitute a vivid record of contemporary Amsterdam life. The greatest artist of the Dutch school, he was a master of light and shadow whose paintings, drawings, and etchings made him a giant in the history of art.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was born on July 15, 1606, in Leiden, the Netherlands. His father was a miller who wanted the boy to follow a learned profession, but Rembrandt left the University of Leiden to study painting. His early work was devoted to showing the lines, light and shade, and color of the people he saw about him. He was influenced by the work of Caravaggio and was fascinated by the work of many other Italian artists. When Rembrandt became established as a painter, he began to teach and continued teaching art throughout his life.

In 1631, when Rembrandt's work had become well known and his studio in Leiden was flourishing, he moved to Amsterdam. He became the leading portrait painter in Holland and received many commissions for portraits as well as for paintings of religious subjects. He lived the life of a wealthy, respected citizen and met the beautiful Saskia van Uylenburgh, whom he married in 1634. She was the model for many of his paintings and drawings. Rembrandt's works from this period are characterized by strong lighting effects. In addition to portraits, Rembrandt attained fame for his landscapes, while as an etcher he ranks among the foremost of all time. When he had no other model, he painted or sketched his own image. It is estimated that he painted between 50 and 60 self-portraits.

In 1636 Rembrandt began to depict quieter, more contemplative scenes with a new warmth in color. During the next few years three of his four children died in infancy, and in 1642 his wife died. In the 1630s and 1640s he made many landscape drawings and etchings. His landscape paintings are imaginative, rich portrayals of the land around him. Rembrandt was at his most inventive in the work popularly known as The Night Watch, painted in 1642. It depicts a group of city guardsmen awaiting the command to fall in line. Each man is painted with the care that Rembrandt gave to single portraits, yet the composition is such that the separate figures are second in interest to the effect of the whole. The canvas is brilliant with color, movement, and light. In the foreground are two men, one in bright yellow, the other in black. The shadow of one color tones down the lightness of the other. In the center of the painting is a little girl dressed in yellow.

Rembrandt had become accustomed to living comfortably. From the time he could afford to, he bought many paintings by other artists. By the mid-1650s he was living so far beyond his means that his house and his goods had to be auctioned to pay some of his debts. He had fewer commissions in the 1640s and 1650s, but his financial circumstances were not unbearable. For today's student of art, Rembrandt remains, as the Dutch painter Jozef Israels said, "the true type of artist, free, untrammeled by traditions."

The number of works attributed to Rembrandt varies. He produced approximately 600 paintings, 300 etchings, and 1,400 drawings. Some of his works are: St. Paul in Prison (1627); Supper at Emmaus (1630); The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632); Young Girl at an Open Half-Door (1645); The Mill (1650); Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer (1653); The Return of the Prodigal Son (after 1660); The Syndics of the Drapers' Guild (1662); and many portraits.

<튈프 박사의 해부학 강의 >해부학 수업을 듣고있는 시청 공무원. 인체에 대한 새로운 발견과 건간한 삶에 대한 관심으로 해부학이 시민 교양강좌, 거의 시청공무원들의 집단초상화.

1632 (110 Kb); Oil on wood, 28 x 34 cm (11 x 13 1/2"); Musee du Louvre, Paris

c. 1635 (120 Kb); Oil on canvas, 167 x 209 cm; National Gallery, London

1655 (20 Kb); Oil on wood; The Louvre

자유를 향한 열망, 네더란드인들의 선조, 그들은 바로 야만적인 모습의 우리 조상들이다. 그리고 그들을 받아들여라! 투박하고 거친 모습.

(이 작품은 이미 내리막길에 있는 렘브란트에세 온 기회, 네덜란드 시청 내부를 장식하고자 대작을 부탁, 그러나 그는,,,)

Peter Paul Rubens

인간을 조각처럼 표현하는 이들과는 달리 인간을 사람처럼 표현한 작가

(70 Kb); Wilton House at Wiltshire, England

1638-40 (150 Kb); Oil on canvas, transferred from panel, 191 x 161.3 cm (75 x 63 1/2 in); Hermitage, St. Petersburg

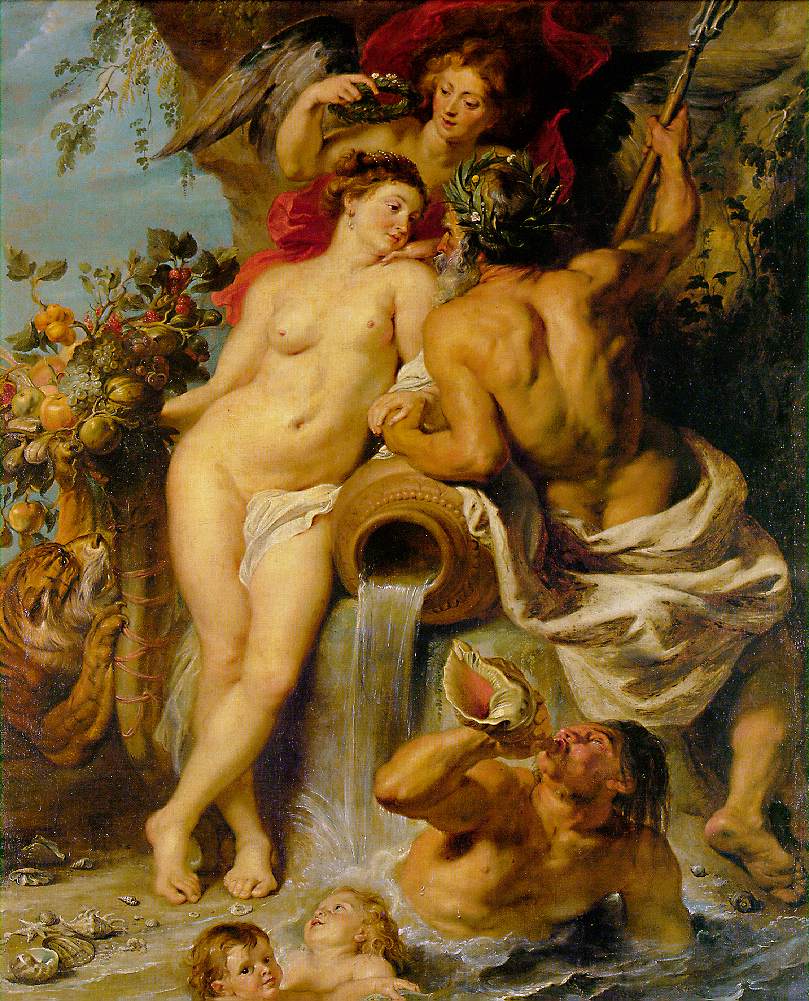

The Union of Earth and Water

c. 1618 (160 Kb); Oil on canvas, 222.5 x 180.5 cm (87 1/2 x 71 in); Hermitage, St. Petersburg

건강하고 아름다운 육체의 표현 또한 바로크 미술의 특징.

1629-30 (180 Kb); Oil on canvas, 203.5 x 298 cm (80 1/8 x 117 1/4 in); National Gallery, London

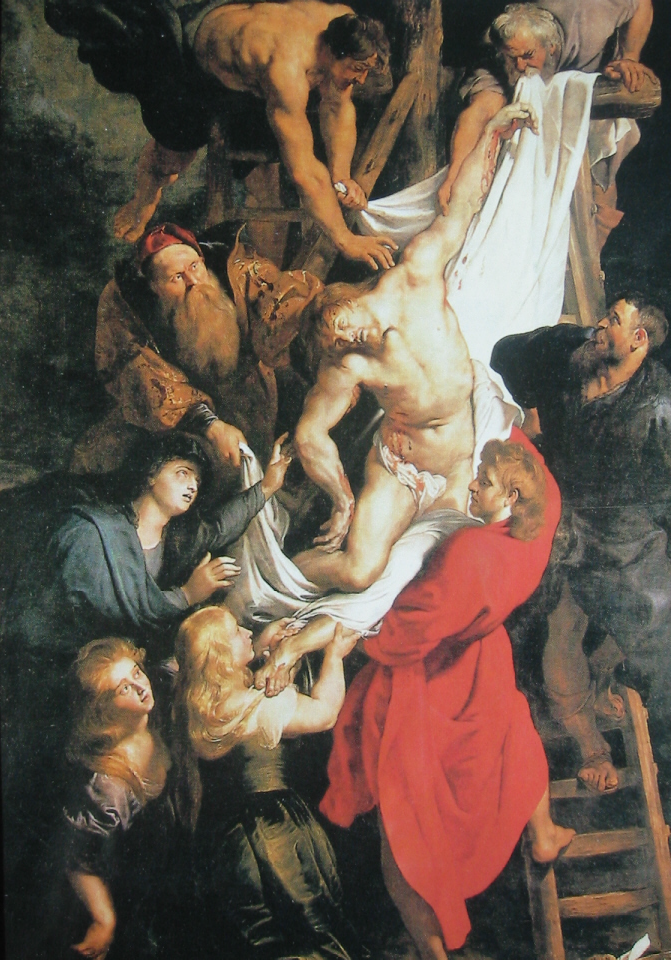

The Descent from the Cross (central part of the triptych). 1611-1614. Oil on panel. Cathedral, Antwerp, Belgium.

레우키포스 딸들의 약탈. 222x209cm.

바로크 작품임을 알 수 있는 폭발적인 힘을 전달하기 위해 대각선 구도. 남성과 여성의 살결을 대조, 그리스 신화에 나오는 제우스 의 쌍둥이 아들 카스토르 와 풀룩스가 두 왕녀를 납치하는 장면. 난폭한 주제임에도 불구하고 큐피드를 등장시켜 극적인 사랑의 세계로...

사랑과 폭력의 양면을 훌륭하게 표현.

<파리스의 심판> 세상에서 가장 아름다운 여자가 황금사과를 차지한다는 예언에 따라 파리스의 심판을 받고있는 헤라, 아테나, 아프로디테.

헤라는 세상을 지배할 수 있는 권력을, 아테나는 전쟁에 나가 두려움을 모르는 용기를, 아프로디테는 세상에서 가장 아름다운 여자를 아내로 주겠다고 약속하며 모두 자기에게 황금사과를 달라고 한다. 파리스는 아프로디테에게 사과를 건네는 순간이다

후에 아프로디테는 파리스에게 남의 아내를 훔치게하고, 그리스와 트로이 사이의 전쟁 도화선이 된다.,

Jan Vermeer

Jan or Johannes Vermeer van Delft

The Kitchen Maid

b. October 1632, d. December 1675, a Dutch genre painter who lived and worked in Delft, created some of the most exquisite paintings in Western art.

성실한 하녀는 성서의 말을 잘 따르는 종. 종교적 교훈을 담아서인지 그가 그린 여인의 모습은 모두 성모마리아처럼 우아하고 아름답다.

His works are rare. Of the 35 or 36 paintings generally attributed to him, most portray figures in interiors. All his works are admired for the sensitivity with which he rendered effects of light and color and for the poetic quality of his images.

Little is known for certain about Vermeer's life and career. He was born in 1632, the son of a silk worker with a taste for buying and selling art. Vermeer himself was also active in the art trade. He lived and worked in Delft all his life. Not much is known about Vermeer's apprenticeship as an artist either. His teacher may have been Leonaert Bramer, a Delft artist who was a witness at Vermeer's marriage in 1653, or the painter Carel Fabritius of Delft. In 1653 he enrolled at the local artists guild. His earliest signed and dated painting, The Procuress (1656; Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden), is thematically related to a Dirck van Baburen painting that Vermeer owned and that appears in the background of two of his own paintings. Another possible influence was that of Hendrick Terbrugghen, whose style anticipated the light color tonalities of Vermeer's later works.

During the late 1650s, Vermeer, along with his colleague Pieter de Hooch, began to place a new emphasis on depicting figures within carefully composed interior spaces. Other Dutch painters, including Gerard Ter Borch and Gabriel Metsu, painted similar scenes, but they were less concerned with the articulation of the space than with the description of the figures and their actions. In early paintings such as The Milkmaid (c.1658; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), Vermeer struck a delicate balance between the compositional and figural elements, and he achieved highly sensuous surface effects by applying paint thickly and modeling his forms with firm strokes. Later he turned to thinner combinations of glazes to obtain the subtler and more transparent surfaces displayed in paintings such as Woman with a Water Jug (c.1664/5; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City).

A keen sensitivity to the effects of light and color and an interest in defining precise spatial relationships probably encouraged Vermeer to experiment with the camera obscura, an optical device that could project the image of sunlit objects placed before it with extraordinary realism. Although he may have sought to depict the camera's effects in his View of Delft (c.1660; Mauritshuis, The Hague), it is unlikely that Vermeer would have traced such an image, as some commentators have charged. Moralizing references occur in several of Vermeer's works, although they tend to be obscured by the paintings' vibrant realism and their general lack of narrative elements. In his Love Letter (c.1670; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), a late painting in which the spatial environment becomes more complex and the figures appear more doll-like than in his earlier works, he includes on the back wall a painting of a boat at sea. Because this image was based on a contemporary emblem warning of the perils of love, it was clearly intended to add significance to the figures in the room.

After his death Vermeer was overlooked by all but the most discriminating collectors and art historians for more than 200 years. His few pictures were attributed to other artists. Only after 1866, when the French critic W. Thore-Burger "rediscovered" him, did Vermeer's works become widely known and his works heralded as genuine Vermeers.

Intimate scenes

Barely 35 works are known to have been painted by Vermeer. His early paintings - mainly history pieces - reveal the influence of the Utrecht Caravaggists. In his later works, however, he produced meticulously constructed interiors with just one or two figures - usually women. These are intimate genre paintings in which the principal figure is invariably engaged in some everyday activity: one is reading a letter, another is fastening a collar about her neck, yet another is pouring out milk. Often the light enters Vermeer's paintings from a window. He was a master at depicting the way light illuminates objects and in the rendering of materials. The Rijksmuseum has three domestic portraits by Vermeer and one street scene: the world-famous Little Street.

With quiet concentration a woman pours milk into a bowl. With her left hand she supports the can she is pouring from. Around her are various objects: a loaf of bread, a stoneware jug, a basket and a brass bucket. The woman is standing near the window so she can see what she is doing. The light falls on her hands; her silhouette is dark against the white wall. There is a fascinating play of light and shadow in this painting. This is one of Johannes Vermeer's genre pieces in which he establishes an intensely intimate atmosphere. Although the artist observes his model from nearby, she continues with her work, totally unperturbed.

Subtle lighting

The lighting in Vermeer's Milkmaid is extraordinarily subtle. Light falls from the left through the window. Beneath and beside the window it is somewhat shadowy, but the woman is standing in full brightness. When you look carefully at the painting you see that Vermeer has introduced tiny points of light all over the canvas: on the edges of the jug and the bowl, but also on the fastening of her yellow dress, and on the bread in the basket. Vermeer paid great attention to details. He has painted tiny rough patches into the texture of the white plasterwork. Also, he gives careful thought to a nail set high in the white wall, as well as to the light entering through a cracked windowpane. The structure of various objects is expertly rendered: gleaming brass and crumbly bread.

Nail with shadow

Cracked windowpane

Brass bucket

Tiny points of light

Simplicity

Clearly, this woman is a servant and no grand lady. Her dress is simple. The blue skirt is tucked up to save it from getting dirty. She wears green over-sleeves which partly protect her yellow bodice. On her head the maid wears a starched cap. She looks strong and sturdy. Vermeer achieves this effect by painting her from a low viewpoint. This lends a certain weight and dignity to this simple and everyday subject - a woman at her work.

Temperance

Perhaps this painting by Vermeer is an embodiment of the virtue of Temperance. The image of a woman pouring out of a jug was sometimes used in this way in the seventeenth century, for example by Jacob de Gheyn II.

Jacob de Gheyn II, Temperance

Space and focal point

Vermeer has carefully organised the space around the maid. This appears from the several overpaintings that can be seen using X-ray and infrared photography. Initially, Vermeer had introduced a painting behind the woman. There was also a sewing basket on the floor beside the footwarmer. In the final version of the picture all these objects were overpainted. The background became less cluttered and the composition was thereby clearer and stronger. The Kitchen Maid is built up along two diagonal lines. They meet by the woman's right wrist. With this trick of composition Vermeer focused the viewer's attention on the act of pouring out the milk.

X-ray photographs of painting

Infrared photo reveals a basket

'Exceptionally good'

Vermeer's Kitchen Maid was highly appreciated at an early date. In an auction catalogue of 1696 the painting is described as follows: A Maid pouring out milk, exceptionally good. The Milkmaid, as the painting is commonly called, was sold for 175 guilders at that auction - a large sum for those days. At the beginning of the twentieth century the painting arrived in the Rijksmuseum. The Rembrandt Society bought the work together with 38 other paintings, thereby saving it for the Dutch public. There was a heated discussion both about the quality of the 39 paintings as well as the price - 750,000 guilders. Many satirical cartoons were published in this connection. Today the painting is unquestionably one of the museum's finest attractions.

Newspaper 'Het Vaderland', 9-11-1907: Minister Rink versus Uncle Sam

Stoneware

Stoneware is made of clay that produces a grey or brown color and is fired at a temperature of around 1250 degrees Celsius. It is exceptionally hard and only slightly porous. Moreover, stoneware does not acquire a taste and is easy to clean. It is therefore an ideal material in which to preserve liquids and from which to drink. Around 1300 stoneware acquired something of a mass market and remained popular until glass and delftware took its place in the 17th century. Sixteenth- and 17th-century stoneware is often decorated with reliefs. One of the centres of stoneware production was the area between Cologne and Aachen in Germany's Rhineland.

Credits: The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

카메라 옵스큐라(어두운 방) -작은 상자에 구멍을 뚫고 렌즈를 붙이면 바깥 풍경이 그림 안에 비치게 되는 광학 도구. 바늘 구멍카메라와 같은 원리. 거울과 간유리를 사용해 이미지를 만듬. 무엇보다 구림구성의 틀을 짜고 명암의 균형을 계산.

모든 재산을 팔아서 진주를 사야한다는 성서의 교훈.비유속의 진주는 하나님의 말씀.

진주 귀고리를 한 소녀는 진리의 말씀을 잘 새기고 실천하면서 사는 올곧은 삶의 자세에 대해 말하고 있다.

(사물의 날카로움이 완화되고, 그림자의 경계가 사라지면서 부드러운 분위기에 안물의 표정도 희미하게 보여진다.)

c. 1665-67; Oil on panel, 22.8 x 18 cm; National Gallery of Art, Washington

Coming upon this painting in the exhibition, the viewer is confronted with an abrupt change from the other works. The Girl with the Red Hat is small even by Vermeer's standards; it is his only known work that was executed on wood panel; and most importantly, its immediacy and intimacy contrast sharply with the meditative mood of the other paintings.

Despite its modest dimensions, a strong visual impact results from the large scale of the girl. Brought close to the picture plane, she communicates directly with the viewer. Her direct gaze and slightly parted lips impart a sense of spontaneity and anticipation. Vermeer relies heavily on color to establish the mood of the work. The red of the hat and the blue of the robe contrast strongly with the muted background. The bright red of the hat advances, heightening the immediacy of the girl's glance, while the blue of the robe recedes, balancing the composition. Vermeer retained warmth in the robe by painting the blue over a reddish-brown ground. The materials - the red hat, robe and chair finials - are animated by highlights of reflected light. Subtle highlights on the girl's eye and mouth animate her expression. Finally, the intense white of the girl's cravat, painted as a thick impasto with parts later chipped off, cradles her face, focusing attention on her expression.

The small size of this work allowed Vermeer to use painstaking detail in its execution. A precise depiction of texture and light is achieved through the duplication of thin glazes over painted ground. To represent the hat, Vermeer firs painted an opaque layer of deep orange red. He then added semi-transparent strokes of light red and orange to render the feathers. The robe highlights allow the underlying blue to show through. With this glaze technique, the underlying layer is used to help model the forms of the composition.

Most scholars agree that Vermeer utilized a camera obscura in the composition and execution of The Girl with a Red Hat. It is possible that he chose a wood panel support to replicate the gloss of a camera obscura image, which was normally projected onto glass. In particular, the diffused specular highlights of the lion head chair finial resemble the unfocused effect of an image seen in a camera obscura. Vermeer expert Arthur Wheelock points out, however, that Vermeer did not simply paint on top of an image projected by a camera obscura. While camera obscura effects were emulated in portions of the painting, in other places, the expected effects are not seen.

Compositional adjustments also contradict the literal reproduction of a camera obscura image. For instance, the left chair finial is larger and angled to the right. If the chair top is extended to the left, it ends up misaligned with the finial. Vermeer adjusted the lines of the chairback to stress the foreground plane of the composition while at the same time, allowing space for the girl's arm to rest.

창문을 통해 들어오는 빛에 더 아름답고 부드럽고 우아해보이는 여인.

The Art of Painting. c.1666-1673. Oil on canvas. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

<회화 예술> 트럼펫과 두꺼운 책을 든 여자는 역사의 뮤즈, 탁자위 물건들은 회화를 습득하기 위한 도구, 바닥의 내진성은 원근법을 암시. 화가는 모델을 보고 그리고, 화가 자신의 모습은 상상으로 표현한 작품. 사생과 상상의 조화.

모델이 베르메르의 아내라는 말도...

앞에 의자는 앉아서 그림을구경하라고 유혹...

당시 그림의 고객은 교양있는 남성 , 마치 그들이 들어와 여인은 고개를숙이고 살포시 미소를 짓는, 화가의모습은 절개선이 많은 최신 유행 의상을 입은 모습.

완전한 완성보다는 부드러운 마무리.

지도 판화 인쇄술, 조각, 타피스트리,,,

17세기 네덜란드의다양한 관심사.

월계관" -명예를중시하는 그림.

c. 1670-72; Oil on panel, 72.2 x 59.7 cm; National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

This masterpiece has been stolen not once, but twice in the last twenty-five years. The owner, a member of Britain's Parliament, was targeted by the IRA, who broke into his estate in 1974 and took a total of nineteen paintings. It was recovered a week later, having sustained only minor damage. In 1986, the Dublin underworld stole the painting. Only after more than seven years of secret negotiations and international detective work was the painting recovered. Hopefully Vermeer's The Concert, recently stolen from the Gardner Museum in Boston, will be recovered in a similar manner.

Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid exemplifies Vermeer's essential theme of revealing the universal within the domain of the commonplace. By avoiding anecdote, by not relating actions to specific situations, he attained a sense of timelessness in his work. The representation of universal truths was achieved by eliminating incidental objects and through subtle manipulation of light, color and perspective.

The canvas presents a deceptively simple composition. The placid scene with its muted colors suggests no activity or hint of interruption. Powerful verticals and horizontals in the composition, particularly the heavy black frame of the background painting, establish a confining backdrop that contributes to the restrained mood.

The composition is activated by the strong contrast between the two figures. The firm stance of the statuesque maid acts as a counterweight to the lively mistress intent on writing her letter. The maid's gravity is emphasized by her central position in the composition. The left upright of the picture frame anchors her in place while the regular folds of her clothing sustain the effect down to the floor. In contrast, the mistress inclines dynamically on her left forearm. Her compositional placement thrusts her against the compressed space on the right side of the canvas. Strong light outlines the writing arm against the shaded wall, reflecting in angular planes from the blouse that contrast abruptly with the regimented folds of the maid's costume. The mistress is painted in precise, meticulous strokes as opposed to the broad handling of the brush used to depict the maid.

The figures, although distinct individuals, are joined by perspective. Lines from the upper and lower window frames proceed across the folded arms and lighted forehead of the maid, extending to a vanishing point in the left eye of the mistress. The viewer's eye is lead first to the maid, then on to the mistress as the focal point of the painting.

Vermeer shuns direct narrative content, instead furnishing hints and allusions in order to avoid an anecdotal presentation. The crumpled letter on the floor in the right foreground is a clue to the missive the mistress is composing. The red wax seal, rediscovered only recently during a 1974 cleaning, indicates the crumpled letter was received, rather than being a discarded draft of the letter now being composed. Since letters were prized in the 17th century, it must have been thrown aside in anger. This explains the vehement energy being devoted to the composition of the response. Another hint is provided in the large background painting, The Finding of Moses. Contemporary interpretation of this story equated it with God's ability to conciliate opposing factions. These allusions have led critics to construe Vermeer's theme as the need to achieve reconciliation, through individual effort and with faith in God's divine plan. This spiritual reconciliation will lead to the serenity personified in the figure of the maid.

c. 1658; Oil on canvas, 49.2 x 44.4 cm; The Frick Collection, New York

c. 1658; Oil on canvas, 54.3 x 44 cm; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In a cobblestone street are two houses with a gate opening onto the passageway between them. A woman sits in an open doorway, busy sewing; two children are playing on the stoop. Soapy water is washing down a small runnel between the paving stones - probably the woman in the passageway has just scrubbed her part of the stoop. Vermeer has recorded this everyday scene with apparent casualness. Although world-famous, not much is known about Vermeer's Little Street. In fact the original location has never been identified, and indeed may never have existed. But more significant is the atmosphere of the picture. The women are diligently employed while the children are absorbed at play. The scene emanates tranquillity and security.

촛점을 맞춘 부분 외에는 사진과 같은 흐린 부분으로, 빛과 어둠의세계로 전환.

3차원의 세계를 평면으로.

Hals, Frans

Pieter van den Broecke c. 1633 (140 Kb); Oil on canvas, 71.2 x 61 cm (28 x 24 in); Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood, London

'History of Arts > Baroque & Rococo' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 로코코 (0) | 2007.10.03 |

|---|---|

| 바로크 - Espagne (0) | 2007.10.02 |

| 바로크- France (2) | 2007.10.01 |

| 바로크 건축 (3) | 2007.10.01 |

| 매너리즘 (1) | 2007.10.01 |