http://www.whitecube.com/exhibitions/jw_new_work/gnd_fl_ii/

The new Jeff Wall show at MOMA has managed to stir the soup pitting those who admire Wall against his detractors. Here's a roundup of show reviews and blog posts (most from the last couple of days).

The new Jeff Wall show at MOMA has managed to stir the soup pitting those who admire Wall against his detractors. Here's a roundup of show reviews and blog posts (most from the last couple of days).

The New York Times profile and show review.

The New Yorker show review.

The Tate mounted Wall retrospective last year. The Tate site includes many images... good to check out for a bit of perspective.

Chris Keeley's thoughtful review.

Wall's show inspired Time to write a somewhat dismissive article on "staged photos". They group Wall with Cindy Sherman, Gregory Crewdson, and AES&F.

Alec Soth's blog entry on the Wall portrait by Justine Kurland in the Times article sparked this interesting discussion on artists doing editorial work.

An article on the Vancouver art scene and Wall's place in it.

Of course there is a wikipedia entry on Wall.

The Landscapist says he likes some of Wall's work but is annoyed by the underlying premise of the work...

Paul Butzi on Wall and 'nowhereness'.

Jon Anderson muses on Wall's constructed images as compared to found images

In Wall's work Dan Ng sees some redemption for creative people in advertising.

Doug Pummer is of two minds on the work...

As for me, I respect Wall. His recent images almost never hit me in the gut as did his earlier ones (sometimes I see the seams of the photoshop trickery which is a turnoff), but he's an important artist with something to say and I pay attention when he makes art... I appreciate the pure richness of his large lightboxes and enjoy decoding his art historical allusions. Much of the criticism of Wall comes from other photographers who find his work somehow threatening. I believe the opposite is true, and that his work has enlarged the range and scope of what people accept as art photography. I'm excited to see the show.Jeff Wall's A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai), 1993.

Jeff Wall is the most exciting kind of contemporary artist—one who engages the past, and lives up to it.

There’s a certain shininess—that buffed light on computer screens, magazines, televisions, and billboards—that’s become inescapable. It’s juicy, too, and stimulates in us a low, Pavlovian desire. Something to buy, see, do? Jeff Wall’s light boxes, which are large backlit color transparencies, momentarily suggest that general cultural shininess. Before we take in his imagery, we sense that everywhere light—the life light of consumer culture—and we expect it to deliver that typically fast gotcha! message. Instead, Wall’s boxes surprise us with a wonderful, otherworldly slowness: We begin to find in them different lights, cues, intimations. They become boxes to open.

Wall is an exciting figure because, to put it bluntly, he hasn’t made the capitulations characteristic of contemporary art. Now the subject of a retrospective organized by Peter Galassi for MoMA and Neal Benezra for SFMoMA (and also the subject of a gallery show at Marian Goodman), Wall, who is 60, seems very much of our moment. Yet he cultivates a living relationship to the great Western tradition, struggles to create rigorous formal compositions, and takes subject matter seriously. All at once. Early in his life he hoped to become a painter, and is particularly known for using traditional paintings as a basis for his own compositions, which he stages and, since the early nineties, sometimes digitally alters. The highly crafted and manipulated A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai) faithfully follows, for example, a composition by the great Japanese artist. Other works draw upon Manet and Cézanne.

Oddly enough, the historical references help give Wall’s art its contemporary presence. Academic thinking today suffuses the practice of art, and Wall’s sensibility reflects this self-conscious knowingness. (He’s catnip for critics.) Yet, because the quotations are fully absorbed and translated into contemporary parlance, his pictures do not become pedantic or retardataire. A Sudden Gust of Wind doesn’t appear especially Japanese; knowing its source is merely important, not vital. Wall seems drawn to the theatrical compositions of the past, and that rich sensation of the staged showpiece, displaced into the present, can send a ghostly echo into our own performance-driven culture. People often complain that Baroque art is “too stagy.” I always think, And we’re not? There can be something beautiful, at once remote and intimate, in a conversation between different stages.

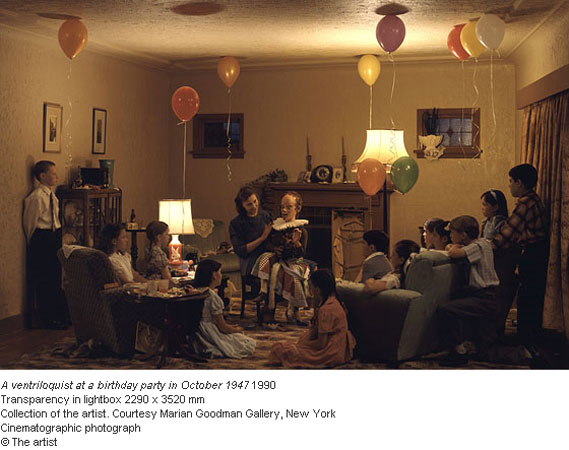

Wall does not let painting-love trap his photographs. He takes inspiration from all over, giving his art enough metaphysical room to breathe; his compositional intensity helps ensure that he does not also succumb to loose pastiche. He’s a student of modern film and of the traditions of photography. In A ventriloquist at a birthday party in October, 1947, he plays with nostalgia and the past. (Memory can be a private stage.) The act of reading may inspire an image; one of his best light boxes, After “Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison, the Prologue, shows a figure, reimagined from the novel, seated in a low room beneath a starry heaven of lightbulbs. He moves among subjects, which also have traditions. He’s at home in the modernist margins—abandoned places, abandoned people—but rarely draws a pointed moral. And he often works with photography’s surrealist edge, where the line between real and fanciful haunts the imagination. In A Sudden Gust of Wind, which is set in a no-there-there landscape, the eruption of the papers and the twirling of the figures has an air of ecstatic release, like a religious visitation. Instead of the Archangel or Virgin, however, the central figure spies his hat soaring upward. Which, by the way, is the best flying hat since Oddjob’s.

Wall isn’t obviously autobiographical: He may depict moments of great release but does not, in his work, fling his personal papers into the air. Instead, he worries about clichés and exhausted traditions. He thinks, judges, observes, weighs, considers. His decisive moment is the decided moment. An artist of this sensibility may seem impersonal to people who prefer a guts-and-glory approach to art. Others will find the detachment refreshing. Wall is not without his desperations. His desire to restore fullness to art—to revive that patient—is just more interesting than the usual soul-baring.

Jeff Wall is the most exciting kind of contemporary artist—one who engages the past, and lives up to it.

There’s a certain shininess—that buffed light on computer screens, magazines, televisions, and billboards—that’s become inescapable. It’s juicy, too, and stimulates in us a low, Pavlovian desire. Something to buy, see, do? Jeff Wall’s light boxes, which are large backlit color transparencies, momentarily suggest that general cultural shininess. Before we take in his imagery, we sense that everywhere light—the life light of consumer culture—and we expect it to deliver that typically fast gotcha! message. Instead, Wall’s boxes surprise us with a wonderful, otherworldly slowness: We begin to find in them different lights, cues, intimations. They become boxes to open.

Wall is an exciting figure because, to put it bluntly, he hasn’t made the capitulations characteristic of contemporary art. Now the subject of a retrospective organized by Peter Galassi for MoMA and Neal Benezra for SFMoMA (and also the subject of a gallery show at Marian Goodman), Wall, who is 60, seems very much of our moment. Yet he cultivates a living relationship to the great Western tradition, struggles to create rigorous formal compositions, and takes subject matter seriously. All at once. Early in his life he hoped to become a painter, and is particularly known for using traditional paintings as a basis for his own compositions, which he stages and, since the early nineties, sometimes digitally alters. The highly crafted and manipulated A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai) faithfully follows, for example, a composition by the great Japanese artist. Other works draw upon Manet and Cézanne.

Oddly enough, the historical references help give Wall’s art its contemporary presence. Academic thinking today suffuses the practice of art, and Wall’s sensibility reflects this self-conscious knowingness. (He’s catnip for critics.) Yet, because the quotations are fully absorbed and translated into contemporary parlance, his pictures do not become pedantic or retardataire. A Sudden Gust of Wind doesn’t appear especially Japanese; knowing its source is merely important, not vital. Wall seems drawn to the theatrical compositions of the past, and that rich sensation of the staged showpiece, displaced into the present, can send a ghostly echo into our own performance-driven culture. People often complain that Baroque art is “too stagy.” I always think, And we’re not? There can be something beautiful, at once remote and intimate, in a conversation between different stages.

Wall does not let painting-love trap his photographs. He takes inspiration from all over, giving his art enough metaphysical room to breathe; his compositional intensity helps ensure that he does not also succumb to loose pastiche. He’s a student of modern film and of the traditions of photography. In A ventriloquist at a birthday party in October, 1947, he plays with nostalgia and the past. (Memory can be a private stage.) The act of reading may inspire an image; one of his best light boxes, After “Invisible Man” by Ralph Ellison, the Prologue, shows a figure, reimagined from the novel, seated in a low room beneath a starry heaven of lightbulbs. He moves among subjects, which also have traditions. He’s at home in the modernist margins—abandoned places, abandoned people—but rarely draws a pointed moral. And he often works with photography’s surrealist edge, where the line between real and fanciful haunts the imagination. In A Sudden Gust of Wind, which is set in a no-there-there landscape, the eruption of the papers and the twirling of the figures has an air of ecstatic release, like a religious visitation. Instead of the Archangel or Virgin, however, the central figure spies his hat soaring upward. Which, by the way, is the best flying hat since Oddjob’s.

Wall isn’t obviously autobiographical: He may depict moments of great release but does not, in his work, fling his personal papers into the air. Instead, he worries about clichés and exhausted traditions. He thinks, judges, observes, weighs, considers. His decisive moment is the decided moment. An artist of this sensibility may seem impersonal to people who prefer a guts-and-glory approach to art. Others will find the detachment refreshing. Wall is not without his desperations. His desire to restore fullness to art—to revive that patient—is just more interesting than the usual soul-baring.

Jeff Wall

27 Nov—19 Jan 2008

Mason's Yard

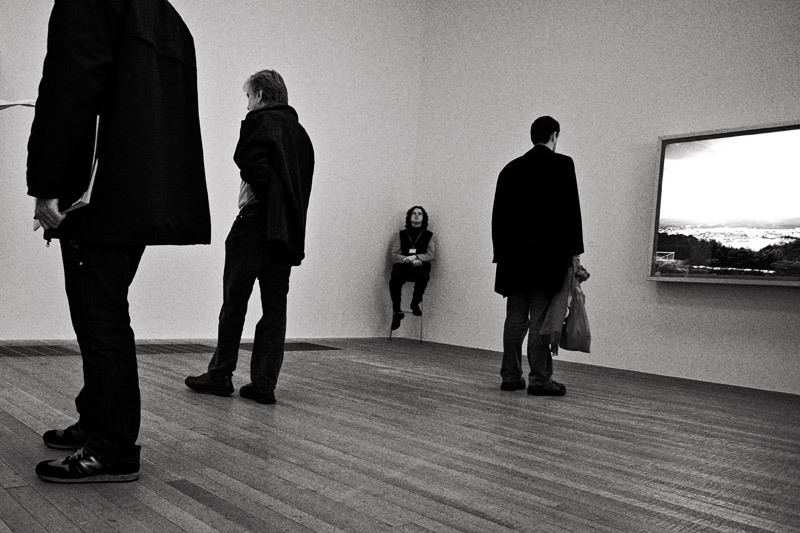

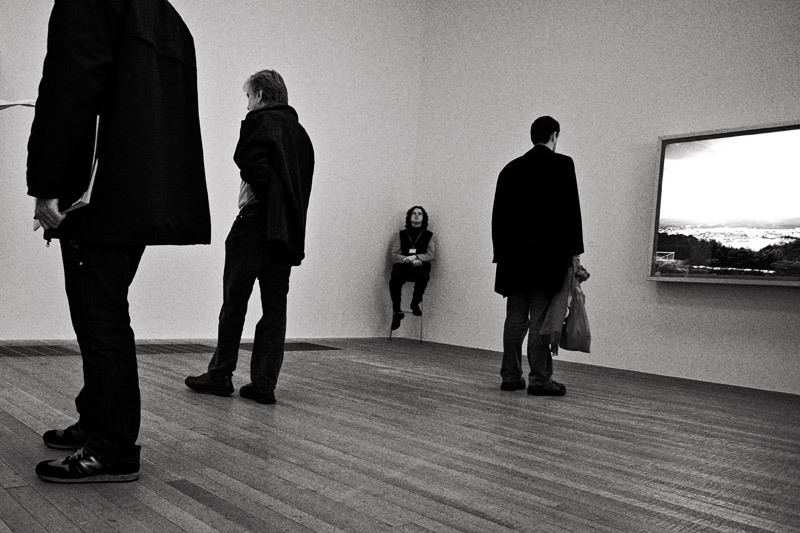

The exhibition of new photographs by Jeff Wall featured six black-and-white pictures and three colour light-boxes. It was the artist’s first exhibition in a private gallery in the UK since showing The Giant at White Cube, Duke Street in 1994, and his first in London since his celebrated retrospective at Tate Modern in 2005. In this recent group of pictures, Wall extends his exploration of the possibilities of realism and what he calls ‘near documentary’ in large-scale photography.

Although Wall is best known for his backlit colour transparencies in light-boxes, for the past decade he has pursued black-and-white photography with equal vigour. The largest of the new pictures, Men waiting, depicts a group of casual labourers clustered together at a gathering point beneath an expansive winter sky. Tenants shows a moment of everyday life in a suburban social housing project. The residents go about their business in a building that looks both timeless – with its clapboard modernism constructed of cheap materials – and temporary. In War game a group of boys turn an empty lot into a field of imaginary battle. Cold storage, Fortified door and Rock surface 1 & 2 are documentary photographs of unoccupied places.

In the light-box works, all documentary photographs, Wall captures the improbable presence of beauty in mundane subjects. Hotels, Carrall Street depicts an inner-city hotel as builders gut it for renovation, while another urban landscape, Church, Carolina St., presents an image of a modest Pentecostal church on a snowy winter day. Dressing poultry shows four people in a cluttered rural building slaughtering chickens and preparing them for market.

Jeff Wall was born in 1946 in Vancouver, Canada, where he lives and works. He has exhibited widely, including group shows ‘Faces in the Crowd: Picturing Modern Life from Manet to Today’, Whitechapel, London (2004), Documenta 11, Kassel, Germany (2002), ‘The Age of Modernism: Art in the 20th Century’, Zeitgeist-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Künste, Berlin (1997), Documenta 10, Kassel, Germany (1997). Solo shows include ICA, London (1984), Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland (1993), Whitechapel, London (2001), Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany (2001), Hasselblad Center, Göteborg, Sweden (2002), Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo, Norway (2004) and retrospectives at Schaulager, Basel (2005), Tate Modern (2005) and MoMA, New York (2007), which travelled to the Chicago Art Institute and is at the SFMoMA, San Francisco, 27 October 2007 – 27 January 2008. ‘Jeff Wall: Exposure’ is at the Deutsche Guggenheim 3 November 2007 – 20 January 2008.

To mark the occasion White Cube published Jeff Wall: Black and White Photographs 1996 - 2007, a catalogue that covers all of Wall’s monochrome pictures to date, with an essay by Craig Burnett.

Jeff Wall’s brilliant stroke when he decided to mount colour photographs the size of paintings on light boxes, like the ones used by advertisers, was to create an art form with the luminous quality of the images we live with everyday on screens — TVs, movies, computer monitors, flat screens, laptops, cellphones, iPhones, video cams.

These days we probably look at lighted images more frequently than any other kind. The screen has become the essential image carrier of modern life. What better vehicle for Wall’s imagery of modern life than an analog of the screen?

It is a very different experience to walk into a museum and see gallery after gallery of monumental lighted images, which on average are six by eight feet. We relate directly to their spectacular sense of reality

I hadn’t thought about this much until I saw Jeff Wall, a travelling exhibition of 41 photographs from 1978 to 2005, at the Art Institute of Chicago, and watched people respond to them. The show opened last February at the Museum of Modern Art in New York last February, closes in Chicago on Sept. 23, and moves to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where it will be on view from Oct. 27 to Jan. 27, 2008. Organized by MoMA and the SFMoMA, the exhibition is the Vancouver-based, internationally renowned Canadian artist’s first retrospective in the United States.

Wall’s photographs draw viewers like magnets to the familiarity of the screen and the surprise of discovering its analog in the museum context. Wall achieved a new form for the still photograph by mounting a transparency in a light box. New as well for still photography in the late 1970s, when Wall began this work, was the monumental size of his images and the fact that they were tableaux arranged for the camera.

It is their luminosity, however, that carries the seductive impact and immediately relates Wall’s photographs to film and other kinds of moving images, which by now are mostly digital.

If a Wall image full of colour and light started to move, one would hardly be amazed, a feeling heightened by the presence of huge black and white photographs in the show. In the late ’70s, Wall was interested in bringing the vocabularies and histories of painting and cinema into photography. His enormously influential work blazed the trail of photoconceptualism and has reshaped the photograph as art.

Looking back, as a retrospective exhibition encourages, it seems Wall was also prescient about the impact of the screen, in all its sizes, on our daily lives.

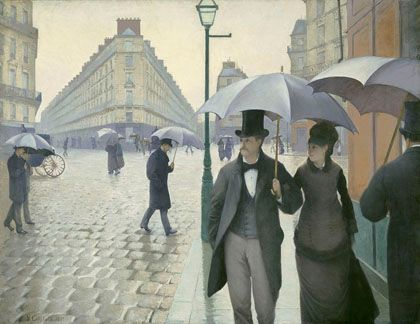

For an exercise in contrast and compare, just look at Wall’s Mimic of 1982 (above) in conjunction with the French Impressionist Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street, Rainy Day of 1877 (below), from the Art Institute’s collection, which influenced Wall's photograph. Both artists choose the portrayal of modern life as their subject and they are worlds apart, although the Caillebotte already shows the influence of photography on art.

Jeff Wall

Jeff Wall is renowned for large-format photographs with subject matter that ranges from mundane corners of the urban environment to elaborate tableaux that take on the scale and complexity of nineteenth-century history paintings.

Wall seized on the idea of producing large, backlit photographs after seeing an illuminated advertisement from a bus window. He had recently been to the Prado, Madrid, and the artist combined his knowledge of the Western pictorial tradition – he had studied art history at London’s Courtauld Institute – with his interest in contemporary media to create one of most influential visions in contemporary art. Wall calls his photographs, after Charles Baudelaire, ‘prose poems’, a description that emphasises how each picture should be experienced rather than used to illustrate a pre-determined idea or a specific narrative. His pictures may depict an instant and a scenario, but the before and after that moment are left completely unknown, allowing them to remain open to multiple interpretations. The prose poem format allows any truth claims of the photograph – the facts we expect from journalistic photography – to remain suspended, and Wall believes that in that suspension the viewer experiences pleasure.

Jeff Wall was born in 1946 in Vancouver, Canada, where he lives and works. He has exhibited widely, including group shows ‘Faces in the Crowd: Picturing Modern Life from Manet to Today’, Whitechapel, London (2004), Documenta 11, Kassel, Germany (2002), ‘The Age of Moderism: Art in the 20th Century’, Zeitgeist-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Künste, Berlin (1997), Documenta 10, Kassel, Germany (1997). Solo shows include ICA, London (1984), Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland (1993), Whitechapel Gallery, London (2001), Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Wolfsburg, Germany (2001), Hasselblad Center, Göteborg, Sweden (2002), Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo, Norway (2004) and retrospectives at Schaulager, Basel (2005), Tate Modern (2005) and MoMA, New York (2007), which travels to the Chicago Art Institute and SFMoMA, San Francisco.

Dead Game; Destroyed Room

After seeing the Jeff Wall exhibit at the AIC I found myself standing in front of this monumental painting by Frans Snyders - Still Life with Dead Game, Fruits and Vegetables in a Market. I marveled at the complexity and modernity of this image. It seemed familiar to me.

Indeed I had seen something similar, maybe an hour earlier. Jeff Wall’s exhibit was filled with imagery like this. Sprawling narratives in a single image. I was invited to walk up close to see the details; then drift further back to take in the whole scene. Small tableaux in the image repay an inquisitive eye. Standing in front of the Jeff Wall photograph The Destroyed Room 1978 provided me the same rewards.The two images have a similar size, similar color palette and a similar structure with both works sweeping the eye of the viewer to the top left of the image. I don’t think that Wall had this particular image in mind when his photograph was created even as I’m sure that Frans Snyders was not prescient in the construction of his, but it is fascinating to me how the two different mediums can create the same sense of wonderment.

As a few examples of the synchronicity in these two images you can see the position of the door and the receeding alleyway; the window and the coppery collander; the diagonal of the deer and of the slashed mattress. If only there were a thief in Wall’s image then the match would be complete. Of equal interest are the professional descriptions of the works. I don’t have the same depth of knowledge of art history, so I rely on what I see rather than what I know. Still, I enjoyed these two works even more through the comparison.

March 8, 2007 12:30

Up Against Jeff Wall

All of this comes in response to Wall's coronation by way of a traveling MoMA retrospective that just opened in Manhattan and an adoring cover story in the New York Times Sunday magazine. (To say nothing of my own humble contribution in Time.)

Early last year I visited Wall in his studio in Vancouver to see what he was up to. What he showed me turned out to be a painstakingly constructed illustration of a scene from a Yukio Mishima novel. That picture confirmed for me my general impression of his paradoxical career. Wall approaches each picture or series of pictures (like his total of three book illustrations) as a way to inquire into a new set of problems. But one thing he does again and again. He uses the anti-art strategies of conceptualism to give himself ideological cover as he re-examines the most retrograde and even sentimental practices of the past. History painting, genre, literary illustration, even "beauty" -- he yearns for them all. He's a resolute modern artist with a longing for the past, a radical softie. And if you're drawn to his pictures at all, and sometimes I am, it's probably because, by way of those practices, he offers pleasures that painting has largely left behind.

But even when he tries to regain the power and pleasures of representational painting, he's careful not to be too easy to grasp. (A shortcoming in a lot of Gregory Crewdson pictures.) In particular, Wall's been interested in a problem that has pre-occupied painters from the time that clear narrative started to leach out of painting in the 19th century -- how to balance meaning and ambiguity. A few bloggers and their readers have shrugged over one of the biggest and most recent images in his MoMA show, In front of a nightclub, 2006, so let me tackle just that one.

This is a picture that's apparently as "pointless" as the most accidental snapshot. But in fact it's an insanely conscientious creation that took weeks of effort, set building, costuming and lighting, all for the purpose of producing a false impression of slice-of-life instantaneousness. Then it invites you to examine this pointless scene -- which he has also blown up to epic size; to the scale of 19th century history painting -- with the equivalent effort.

What we can learn from the most formless moments of life and how to learn from them is a longstanding preoccupation of art. I mentioned a few weeks ago that I had been reading Milan Kundera's new book length essay about fiction called The Curtain, in which he argues that sifting through the quotidian is one ofthe most important things the novel can do. Something he says in there reminded me of Wall's picture. "The novel alone could reveal the immense mysterious power of the pointless." The novel alone? Maybe not. Pictures make the attempt all the time. I think this is what Garry Winogrand was after towards the end of his life, when he sometimes simply hung his camera out the window of a moving car and took pictures of everything that went by.

One other thing. Interweaving layers of reality and falsehood are a post-modern obsession but by no means something that the post-modern '70s ushered in. For one thing, the fluctuations between reality and fiction in Wall's Nightclub picture remind me of Shakespearean theatre. I mean actual Shakespearean theater, at the time of Shakespeare, when adolescent boys played all of the women's roles. Which means that in, say, Tweflth Night, in the scenes in which the lady Olivia falls in love with "Cesario", who is in fact the lady Viola disguised as a boy, what the Elizabethan audience was seeing was a boy pretending to be Olivia courting a boy pretending to be a woman who was pretending to be a boy. Which means a boy pretending to be a boy. You do the math.

Final point. For the record, there is no substitute for painting. And no substitute for photography either.

'Exhibition > Photography&Media' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 네덜란드 작가 엘코 블랑 (Eelco Brand, 1969) (1) | 2008.03.28 |

|---|---|

| 도시의 감성지수 (0) | 2008.03.01 |

| ~SANDY SKOGLUND (0) | 2008.02.23 |

| 국제사진 1900~1950 (0) | 2008.02.22 |

| 노정하 (0) | 2008.02.19 |